Introduction

Historically European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) guidelines recommended laparoscopy with histology to provide a confirmatory diagnosis of endometriosis, however negative histology did not necessarily exclude disease.1 Laparoscopic surgery, however, comes with increased risk and notably greater cost when compared to non-invasive imaging techniques and clinical examination, which are currently recommended as the first diagnostic step in the 2022 updated guidelines. Indeed, diagnostic laparoscopies can cost upwards of several thousand dollars, and surgical procedures have been found to be a major driver for inpatient-associated direct costs to endometriosis patients.2 Despite their demonstrated success however, certain techniques may be more or less applicable in specific clinical situations, or for different types of disease. Given the recent changes to the ESHRE guidelines, and unique presentation of each patient, it is important to be aware of the current diagnostic algorithm, approaches and techniques for diagnosis, and when their use is most appropriate.

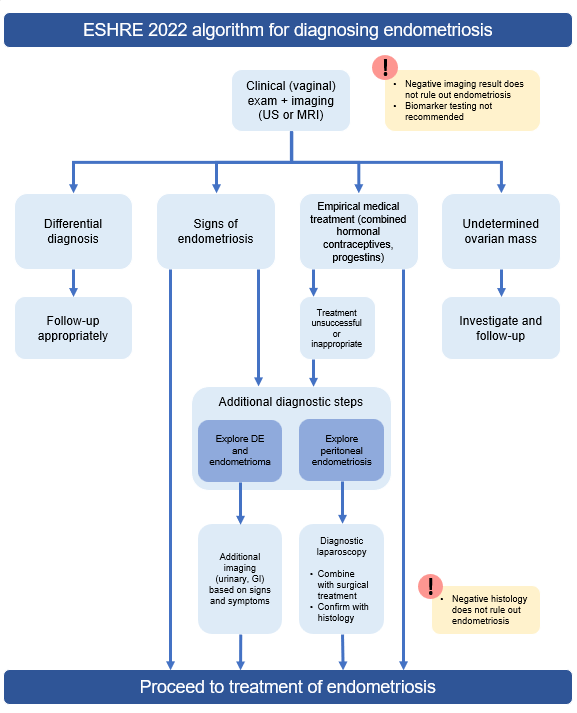

ESHRE 2022 – Updated Algorithm

Algorithm: include image from guidelines

Clinical pelvic examination is strongly recommended by the current ESHRE 2022 guidelines, and entails the palpitation of the abdomen, alongside physical examination of the pelvis. The physical includes a number of digital examinations, including inspection of the vagina for retraction, dark nodules, and potential bladder involvement, inspection of the retrocervical area for infiltration to regions such as the uterosacral ligaments or pouch of Douglas, and recto/vaginal palpitation to determine involvement of the rectum and surrounding visceral pelvic fascia.3,4 This is comparatively the most cost-effective approach to begin a diagnostic work-up, however it is important to note there are caveats. Diagnostic accuracy has historically been low, with several retrospective and prospective reports citing sub-50% sensitivity.4 Even more recent systematic reviews report the pooled sensitivity of pelvic examination for deep endometriosis is 71%, and pooled specificity is 69%.5 Diagnosis via clinical pelvic examination therefore continues to be variable, due potentially to differential symptom severity unrelated to disease stage, and/or pain caused by the examination itself. Indeed, studies have shown patients with deep endometriosis experience significantly greater painful muscle spasms during physical examination compared to patients with no signs of endometriosis, and there are situations in which a physical exam may not be the most appropriate (eg, due to age, religion, prior abuse, etc.).3,4,6 In situations where the results of a pelvic examination remain unclear, or the examination itself is not applicable, additional imaging approaches may be used.

Imaging via transvaginal ultrasound (US), 3D ultrasound, rectal endoscopic sonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used alongside a clinical exam for potential endometriosis. US and MRI specifically, are strongly recommended by ESHRE 2022 guidelines, with varying diagnostic accuracy in superficial pelvic endometriosis, ovarian endometrioma (OA), and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).4 A 2016 review by Nisenblat et al. highlights that for pelvic endometriosis, neither MRI nor US exhibited superiority over laparoscopy, however US did have overall good specificity at 95%.7,8 US and MRI did, however, appear to have greater diagnostic utility for OA and DIE subtypes. For OA, US specificity was 96%, and sensitivity was 93%.7 These findings continue to be supported by additional reviews and studies, reporting specificities and sensitivities as high as 96% for US in OA.9,10 Nisenblat et al. highlight the use of MRI for OA also has high sensitivity and specificity at 91% and 95%, respectively. These results are similarly supported by more recent reviews highlighting up to 93% sensitivity and 94% specificity.7,10 For DIE, Nisenblat et al’s review highlights US had an overall sensitivity of 79% and specificity or 94%; results similarly found in Zhang et al’s 2020 review reporting a sensitivity and specificity of 76% and 94%, respectively. In Nisenblat et al’s review, sensitivity of MRI for DIE was higher, at 94%, despite low specificity at 77%; whereas Zhang et al’s study reports sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 87%, respectively.5,7 Nisenblat et al reported for OA, transvaginal US and MRI approached and met criteria for a replacement test, respectively; and MRI approached criteria as a replacement test for DIE.7 Zhang et al’s 2020 review continued to support the utility of these two approaches for DIE, where both US and MRI were found to have higher diagnostic accuracy than physical examination alone, with an AUC of 0.92 and 0.91 respectively (versus 0.76 for physical exam.5 When evaluating adolescent patients, special considerations should be made based on the patient’s age and cultural background, wherein a transvaginal US may not be appropriate. In such a scenario, guidelines highlight alternatives, including MRI, transabdominal, transperineal, or transrectal scans.4

It is important to note that US is comparatively a more cost-effective and routine procedure in primary care, whereas MRI may require more specialized follow-up and referral. Furthermore, a negative result does not rule-out endometriosis. In the event of a negative US or MRI result despite continued symptoms, guideline recommended follow-up steps include empirical medical treatment, additional imaging of urinary and digestive systems for DIE or OA, and diagnostic laparoscopy.3,4

Imaging: Maybe add a set of images for different modalities? Eg, addressing what OA and DIE endometriosis look like on US versus MRI (2 main modalities in guidelines); leave out peritoneal b/c it did not approach replacement? ß May need to request/consult with AbbVie and/or KOL?

Empirical treatment and laparoscopy are highlighted in recent guidelines as potential follow-up steps for patients who have had negative imaging results. While laparoscopy with confirmational histology has historically been considered the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis, it comes with notably higher costs and risks. Empirical treatment, on the other hand, serves to support a diagnosis through the improvement of symptoms in response to first-line treatment with oral contraceptives or progestogens (to be outlined in a subsequent brief).4 Guidelines highlight that neither empirical treatment nor laparoscopy are superior in this context, each coming with their own advantages and caveats. Clinicians must therefore work with patients to determine the next best step for diagnosis based on their unique needs and risk tolerance.4

Biomarker use is strongly recommended against in current ESHRE 2022 guidelines, including analysis of endometrial tissue, blood, urine, menstrual, or other uterine fluids.4 Guidelines highlight that while there is a large body of research, negative results are unlikely to be published resulting in publication bias, and several systematic reviews have revealed studies of questionable quality with unreliable results.4 CA-125, while not recommended for diagnostic purposes, is reviewed as a potential screen, however while it has been shown to have a high specificity of 93%, overall sensitivity is low at around 52%.4 CA-125 testing is widely available at a minimal cost, however this test is typically used as part of the diagnostic work-up for ovarian cancer. A positive result may therefore increase physician suspicion of endometriosis, but at the cost of increased anxiety to the patient; and furthermore, a negative result still does not exclude the possibility of disease. The Guideline Development Group, therefore, conveys larger multicenter studies are needed, in order to more thoroughly examine the potential diagnostic feasibility and utility of biomarkers in endometriosis.4

Long-term monitoring is given only a weak recommendation by current ESHRE guidelines, as the evidence base to support its long-term benefit has not yet been properly established. As seen in evaluation procedures for primary diagnosis, biomarkers are similarly not recommended for long-term monitoring of recurrence, where analysis of CA-125 have proven unreliable or inconsistent across prior literature. Imaging too, presents unique challenges, where US may be used to monitor OA, but not superficial peritoneal endometriosis, which is only best detected via laparoscopy. Guidelines highlight while the appropriate frequency and modality for follow-up is not yet known, that physical examination alongside mental impact should continue to be considered as a mainstay for evaluation due to the unique presentation and disease course of each patient.4

Conclusion

Endometriosis can be challenging to diagnose due to the non-specific nature of certain symptoms, a lack of correlation with disease severity, and an absence of any validated molecular test to reliably detect disease. The diagnostic process begins with a clinical pelvic examination, including both digital exam followed by imaging, where ultrasound and MRI have the strongest evidence base supporting their use. While diagnostic laparoscopy has historically been the gold standard, MRI and ultrasound come with reduced costs, mortality, and morbidity, and are therefore recommended in updated guidelines as the first step alongside a clinical exam. It is important to note that in certain populations (eg, adolescent, or those with trauma), pelvic exams and transvaginal imaging may not be appropriate. In these cases, alternative imaging methods such as MRI should be considered. Negative imaging results, however, do not rule out the presence of endometriosis, and available follow-up options include empirical treatment with oral contraceptives or progestogens, and diagnostic laparoscopy with confirmational histology. Due to the variable presentation of endometriosis, and the unique needs of each patient, shared decision-making between patient and clinician is encouraged to provide tailored and optimal patient outcomes.4

1. Dunselman GAJ, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457.

2. Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, Kelley C, Winkel C. The direct and indirect costs associated with endometriosis: A systematic literature review. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(4):712-722. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev335. Accessed 8/29/2023. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev335.

3. Bazot M, Daraï E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: Clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):886-894. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.10.026.

4. Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022;2022(2):hoac009. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac009.

5. Zhang X, He T, Shen W. Comparison of physical examination, ultrasound techniques and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(4):3208-3220. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9043.

6. Dos Bispo APS, Ploger C, Loureiro AF, et al. Assessment of pelvic floor muscles in women with deep endometriosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294(3):519-523. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4025-x.

7. Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PMM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2(2):CD009591. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009591.pub2.

8. Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Khan KS. Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: A systematic quantitative review. BJOG. 2004;111(11):1204-1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00433.x.

9. Alborzi S, Rasekhi A, Shomali Z, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal, and transrectal ultrasonography in deep infiltrating endometriosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(8):e9536. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009536.

10. Baușic A, Coroleucă C, Coroleucă C, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound vs. magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) value in endometriosis diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(7):1767. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12071767. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12071767.