Introduction

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent gynecologic disease with an elusive mechanistic etiology, resulting in the outgrowth of endometrial tissue beyond the uterus onto other organs such as the fallopian tubes, ovaries, bladder, ureter, and distal regions of the body within the peritoneal cavity.1 While benign in nature, endometriosis is often painful and debilitating, adversely affecting patients both economically and socially through missed work, school, and family time.2 It also causes infertility, which can have a devastating effect on quality of life, lead to depression and/or feelings of inadequacy. Those who choose to try to conceive often require invasive, expensive, and even painful treatment, including interventions to remove endometriotic lesions and subsequent fertility treatments.

Reports on the prevalence vary, with early studies citing a global statistic of about 10%, and more recent systematic analyses yielding rates from 1%-18%.3-6 This wide range may be due to the variable presentation of endometriosis, spanning from asymptomatic to severe and debilitating, and differentially affecting women of certain age groups and geographic regions.3,4 Given the profound impact endometriosis can have on a patient’s overall quality of life, it is important to be aware of the types and symptoms of endometriosis in order to provide timely diagnosis and care.

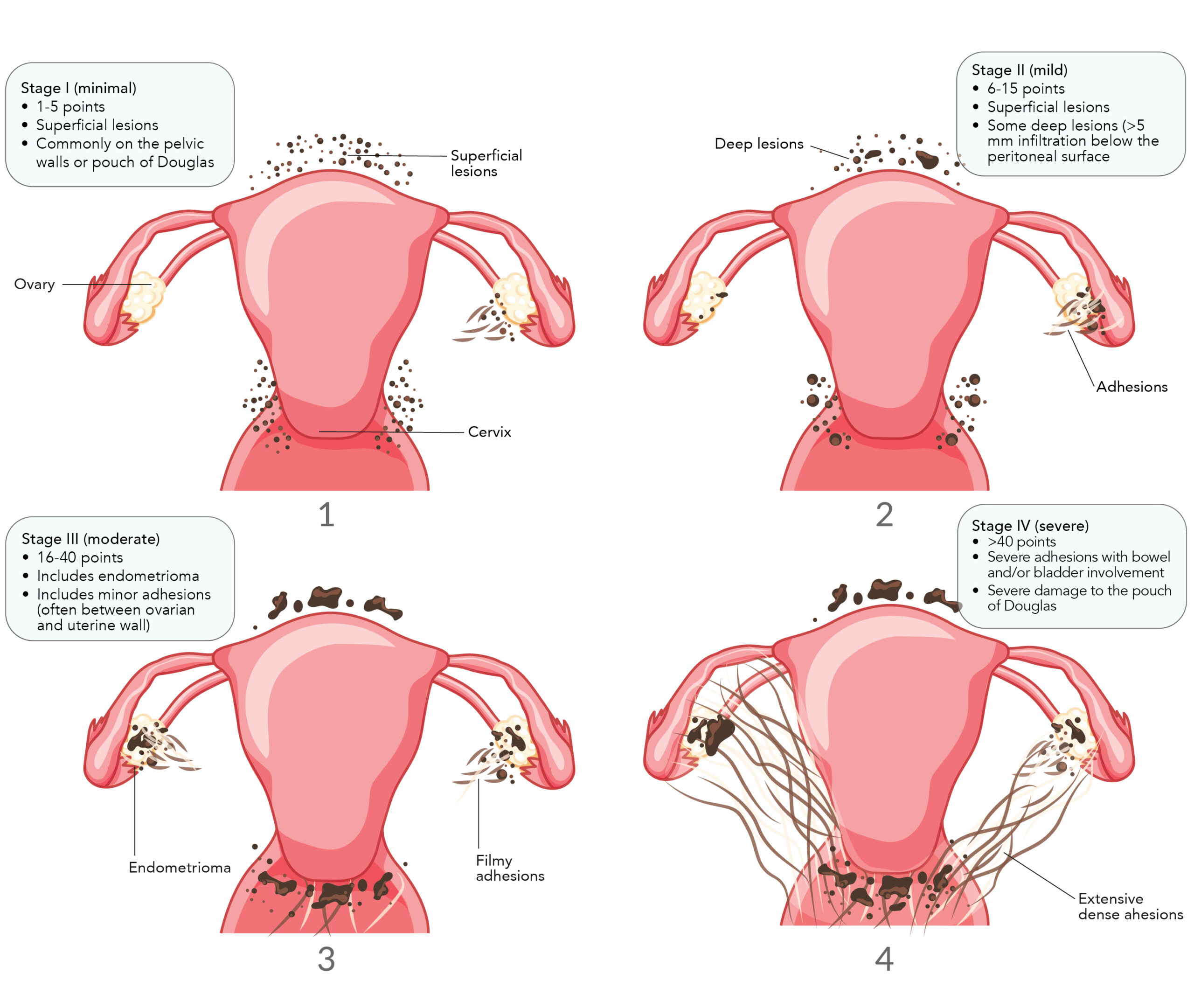

According to the widely accepted revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) criteria, there are four stages of endometriosis determined via a point system that takes into account the size and extent of endometrial implants and ovarian endometriomas, in addition to the severity of adhesions:7,8

- Stage I: Minimal disease, with few superficial implants and mild filmy adhesions

- Stage II: Mild disease containing a greater amount of slightly deeper implants and mild filmy adhesions

- Stage III: Moderate disease, consisting of small ovarian endometriomas on one or both ovaries, with many deep implants and severe dense adhesions

- Stage IV: Severe disease, with large ovarian endometriomas, many deep implants and severe dense adhesions, where the rectum may adhere to the uterus (image ref)

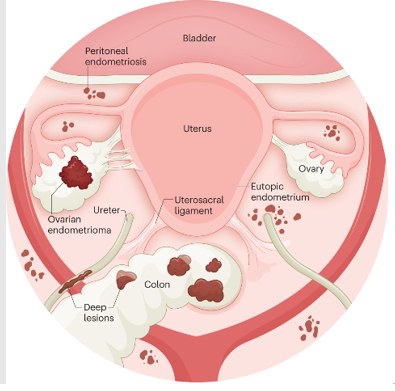

The three types of endometriosis include superficial peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometrioma, and deep infiltrating endometriosis. These occur in distinct regions of the abdomen through varying proposed mechanisms.9 (image ref)

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis occurs in an estimated 15%-50% of women with endometriosis.10 Characterized by the formation of endometriotic lesions on the peritoneum, this particular form of disease is hypothesized to result from retrograde menstruation wherein uterine contractions force endometrial tissue through the fallopian tubes into the body cavity.11 These lesions, in turn, release neurotrophic factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines thought to trigger a ‘neurogenic inflammatory’ signaling cascade, whereby cyclical pain due to hormonal fluctuation eventually converts to chronic pelvic pain through the formation of vascularized, innervated lesions.12-14

Ovarian endometrioma (OMA) affects an estimated 17%-44% of women with endometriosis, occurring nearly twice as often in the left ovary compared to the right ovary.15,16 Accounting for roughly 35% of all benign ovarian cysts, ovarian endometriomas are enveloped in endometrial tissue often containing thick, brown fluid, earning them the moniker “chocolate cysts.”9,15,17 The etiology remains unclear, and three frequently proposed hypotheses include invagination of the ovarian cortex containing endometriotic implants, invasion of the corpus luteum by superficial endometriotic implants, and metaplasia of invaginated ovarian celomic epithelium.9,15

Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is estimated to affect 20% of patients with endometriosis.18 As the most aggressive form of endometriosis, DIE is characterized by invasion of the peritoneum beyond 5mm in depth, or progression to other organs such as the intestines (eg bowel, rectovaginal septum) or urinary system (eg ureters, bladder).19,20 There are several hypotheses for the formation of DIE as well, including dormant retrograde menstruation, differentiation of endometrial stem cells, or conversion of superficial endometriosis to DIE via genetic and epigenetic changes in gene expression characteristic of cancer.20 The later theory is supported by findings that show DIE tissue is resistant to apoptosis and grows increasingly proliferative in environments of high oxidative stress.20,21

Overarching symptoms of endometriosis include cyclical or non-cyclical abdominopelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, dysuria, dyspareunia, dyschezia, hematuria, rectal bleeding, pneumothorax, chest pain, and shoulder pain.18 Patients with endometriosis are also more likely to have co-morbid conditions such as fibromyalgia, migraine, depression, irritable bowel syndrome, or even additional non-malignant gynecologic diseases like uterine fibroids or adenomyosis.22,23 Symptom presentation varies widely, where up to 25% of patients can be asymptomatic, and studies show inconclusive or little evidence of the predictive power these symptoms alone may have in diagnosing or staging endometriosis.18,24,25 Guidelines do, however, recommend clinicians consider endometriosis in patients presenting with these symptoms, highlighting the presence of multiple symptoms may be more strongly suggestive of potential disease.18

Symptoms may vary in presentation depending on the subtype of endometriosis in question. DIE, for example, exhibits different symptoms depending on the affected organ(s), where involvement of the bladder typically results in increased urination frequency, urination urgency, dysuria, or hematuria; involvement of the bowel causes bloating, diarrhea, constipation, cramping, and painful defecation; and involvement of the uterosacral ligaments or pouch of Douglas yields more commonly known symptoms such as dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and chronic pelvic pain.26 More recent studies show patients with DIE also experience higher rates of dysmenorrhea compared to those with OMA only (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.02-7.70), alongside higher rates of heavy menstrual bleeding (OR 1.61, 95% CI 0.65-3.98).27 For OMA, on the other hand, research on associated pain has been historically limited, and continues to remain so. A 2010 study examining OMA in a retrospective cohort of 350 cases spanning 25 years revealed pain was reported nearly twice as much in those patients with coexisting peritoneal endometriosis compared to those with OMA only. Patients with OMA only were also notably more likely to report no pain, at a rate of 61.7%, whereas only 14.6% of patients with OMA with peritoneal lesions had no pain complaints.28 Mechanistically, authors highlight increased macrophage recruitment in patients with coexisting peritoneal lesions indicative of a pro-inflammatory tissue microenvironment, alongside increased PGF2α and COX2 activity, both of which may act in concert to promote uterine contraction and pain sensitivity, respectively.28 Pain, therefore, appears to be prevalent in patients with peritoneal or DIE disease; however, studies have revealed symptoms like infertility also occur more frequently in those with peritoneal involvement compared to OMA alone.29 As pain continues to be a symptom experienced uniquely by each patient, guidelines have highlighted the potential benefit of symptom diaries for objectifying pain and demonstrating symptoms.18 Where available, these may have utility in guiding clinical suspicion of endometriosis and prompting subsequent diagnostic workup.

Endometriosis symptoms can often seem broad or overlap with other diseases such as pelvic inflammatory disease and irritable bowel syndrome.30 Furthermore, symptom severity is not correlated with disease stage, and as mentioned, many patients remain asymptomatic. These factors, combined with the overall social stigma surrounding the discussion of gynecologic disease, serve as consistent barriers to a timely endometriosis diagnosis that can have significant negative, long-term impacts on overall patient quality of life.18,22

Early data from the international, multicenter World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF) EndoCost study revealed a mean delay for diagnosis of 5.5 years from symptom onset, where patients saw an average of 3 physicians before receiving a confirmatory diagnosis.31 Endometriosis was found to profoundly affect patient quality of life, where 16% of participants reported time lost to education and 51% experienced an impact to their job. Of the 931 participants, 50% conveyed endometriosis negatively impacted relationships, with 10% even citing this as a contributing factor to their divorce.31 Later studies reveal women with endometriosis experienced a loss of workplace productivity totaling on average 6.3 hours per week, where the majority of this was due to presenteeism. Productivity at home also continues to be affected, where women experienced a loss of household productivity averaging 4.9 hours per week. The number of symptoms experienced correlated with lost productivity, where women with 3 or more concurrent symptoms exhibited greater absenteeism and presenteeism compared to those who experienced 2 symptoms or less.32 Interestingly, quality of life has also been shown to vary by endometriosis subtype, where patients with DIE experience greater negative impacts to their emotional health, self-determination, self-image, and social environment, when compared against patients having only peritoneal or ovarian disease.33 Finally, lost productivity combined with healthcare costs result in a significant economic burden for endometriosis patients. In the United States in particular, patients experience a loss of roughly $12,000/year due to medical bills, and $16,000/year due to lost productivity.34 Pain is a significant contributing factor, where patients with severe pain experience a nearly 13-fold increase in yearly costs compared to those with only minimal pain.35

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a disease with complex symptomology and unclear etiology, making this a challenging condition to navigate for affected patients. Lengthy diagnostic delays can allow for progression and exacerbated symptoms, in which pain plays a major role, negatively impacting quality of life in a variety of ways. Patients experience lost productivity in school, work, and at home, where social relationships may also be strained. Increased awareness of the symptoms of endometriosis is therefore needed, such that practitioners can suspect and evaluate for this disease at earlier stages to facilitate prompt intervention.

1. Smolarz B, Szyłło K, Romanowicz H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis, treatment and genetics (review of literature). Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10554. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910554. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910554.

2. As-Sanie S, Black R, Giudice LC, et al. Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(2):86-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.033.

3. Sarria-Santamera A, Orazumbekova B, Terzic M, Issanov A, Chaowen C, Asúnsolo-Del-Barco A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence and prevalence of endometriosis. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;9(1):29. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010029. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010029.

4. Moradi Y, Shams-Beyranvand M, Khateri S, et al. A systematic review on the prevalence of endometriosis in women. Indian J Med Res. 2021;154(3):446-454. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_817_18.

5. Houston DE, Noller KL, Melton LJ3, Selwyn BJ, Hardy RJ. Incidence of pelvic endometriosis in rochester, minnesota, 1970-1979. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125(6):959-969. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114634.

6. Eisenberg VH, Weil C, Chodick G, Shalev V. Epidemiology of endometriosis: A large population-based database study from a healthcare provider with 2 million members. BJOG. 2018;125(1):55-62. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14711.

7. Curtis L. Endometriosis: From identification to management. Clinician Reviews. ;27(5):28-32. https://www.mdedge.com/clinicianreviews/article/136650/womens-health/endometriosis-identification-management/page/0/1.

8. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis: A guide for patients. 2016.

9. Imperiale L, Nisolle M, Noël J, Fastrez M. Three types of endometriosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. state of the art. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):994. doi: 10.3390/jcm12030994. doi: 10.3390/jcm12030994.

10. Hudelist G, Ballard K, English J, et al. Transvaginal sonography vs. clinical examination in the preoperative diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(4):480-487. doi: 10.1002/uog.8935.

11. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(5):261-275. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.255.

12. Godin SK, Wagner J, Huang P, Bree D. The role of peripheral nerve signaling in endometriosis. FASEB Bioadv. 2021;3(10):802-813. doi: 10.1096/fba.2021-00063.

13. Asally R, Markham R, Manconi F. The expression and cellular localisation of neurotrophin and neural guidance molecules in peritoneal ectopic lesions. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(6):4013-4022. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1348-6.

14. Dückelmann AM, Taube E, Abesadze E, Chiantera V, Sehouli J, Mechsner S. When and how should peritoneal endometriosis be operated on in order to improve fertility rates and symptoms? the experience and outcomes of nearly 100 cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;304(1):143-155. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-05971-6.

15. Gałczyński K, Jóźwik M, Lewkowicz D, Semczuk-Sikora A, Semczuk A. Ovarian endometrioma – a possible finding in adolescent girls and young women: A mini-review. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12(1):104-5. doi: 10.1186/s13048-019-0582-5.

16. Matalliotakis IM, Cakmak H, Koumantakis EE, Margariti A, Neonaki M, Goumenou AG. Arguments for a left lateral predisposition of endometrioma. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):975-978. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.059.

17. Levy, Barbara, Barbieri, Robert. Endometriosis: Management of ovarian endometriomas – UpToDate. . . https://www.uptodate.com/contents/endometriosis-management-of-ovarian-endometriomas. Accessed Aug 24, 2023.

18. Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, Horne A, Jansen F, Kiesel L, King K, Kvaskoff M, Nap A, Petersen K, Saridogan E, Tomassetti C, van Hanegem N, Vulliemoz N, Vermeulen N, ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Group. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022(2). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35350465/. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac009.

19. Wu L, Li J. Malignant transformation of deep infiltrating endometriosis with invasion of the rectum in a 34-year-old woman. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2023;46(7):2999-3000. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1015958423002221. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2023.02.024.

20. D’Alterio MN, D’Ancona G, Raslan M, Tinelli R, Daniilidis A, Angioni S. Management challenges of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Int J Fertil Steril. 2021;15(2):88-94. doi: 10.22074/IJFS.2020.134689.

21. De Paula LB, Braga NP, Mendonça M, Moro L, Geber S. Apoptosis of ectopic endometrial cells is impaired in women with endometriosis. Journal of Endometriosis. 2012;4(1):17-20.

22. As-Sanie S, Black R, Giudice LC, et al. Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(2):86-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.033.

23. Horne AW, Missmer SA. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis. BMJ. 2022;379:e070750-070750. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070750.

24. Al Shukri M, Al Riyami AS, Al Ghafri W, Gowri V. Are there predictors of early diagnosis of endometriosis based on clinical profile? A retrospective study. Oman Med J. 2023;38(1):e458. doi: 10.5001/omj.2023.35.

25. Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A. Endometriosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(8):441-447. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9436-1.

26. D’Alterio MN, D’Ancona G, Raslan M, Tinelli R, Daniilidis A, Angioni S. Management challenges of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Int J Fertil Steril. 2021;15(2):88-94. doi: 10.22074/IJFS.2020.134689.

27. Yuan X, Wong BWX, Randhawa NK, et al. Factors associated with deep infiltrating endometriosis, adenomyosis and ovarian endometrioma. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2023;52(2):71-79. doi: 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2022334.

28. Khan KN, Kitajima M, Fujishita A, et al. Pelvic pain in women with ovarian endometrioma is mostly associated with coexisting peritoneal lesions. Hum Reprod. 2012;28(1):109-118. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des364. Accessed 8/24/2023. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des364.

29. Aliani F, Ashrafi M, Arabipoor A, Shahrokh-Tehraninejad E, Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S, Akhond MR. Comparison of the symptoms and localisation of endometriosis involvement according to fertility status of endometriosis patients. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;38(4):536-542. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1374933.

30. Penrod N, Okeh C, Velez Edwards DR, Barnhart K, Senapati S, Verma SS. Leveraging electronic health record data for endometriosis research. Front Digit Health. 2023;5:1150687. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1150687.

31. De Graaff AA, D’Hooghe TM, Dunselman GAJ, et al. The significant effect of endometriosis on physical, mental and social wellbeing: Results from an international cross-sectional survey. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(10):2677-2685. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det284.

32. Soliman AM, Coyne KS, Gries KS, Castelli-Haley J, Snabes MC, Surrey ES. The effect of endometriosis symptoms on absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace and at home. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(7):745-754. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.7.745.

33. Tiringer D, Pedrini AS, Gstoettner M, et al. Evaluation of quality of life in endometriosis patients before and after surgical treatment using the EHP30 questionnaire. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):538-3. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-02111-3.

34. Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, Kelley C, Winkel C. The direct and indirect costs associated with endometriosis: A systematic literature review. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(4):712-722. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev335.

35. Armour M, Lawson K, Wood A, Smith CA, Abbott J. The cost of illness and economic burden of endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain in australia: A national online survey. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223316.