Introduction

Endometriosis-related pain can take many forms, including chronic pelvic pain that is cyclical or non-cyclical, dyspareunia, dysuria, and dyschezia. These collectively can have lasting, negative consequences on patient quality of life (QoL). While analgesics like NSAIDs are a frequent go-to strategy in treating pain, these can cause significant gastrointestinal side effects limiting their long-term use. Hormone treatment, therefore, is strongly recommended by the 2022 European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) guidelines for the treatment of pain in endometriosis. Combined hormonal contraceptives and progestins are recommended for first-line treatment, however roughly 1/4 to 1/3 of patients may not respond, exhibiting ‘progesterone resistance’.1 In such cases, second-line options like gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists are recommended, the latter of which representing a new addition to updated guidelines. Given the recent updates to the ESHRE guidelines, it is important to be aware of the existing, discontinued, and emerging therapies for the treatment of endometriosis-related pain, and in which scenarios their application is best suited.

Analgesics such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and neuromodulators (eg, SSRI, anticonvulsants) are only weakly recommended by the current 2022 ESHRE guidelines, due to limited available evidence of their efficacy in treating endometriosis pain2 . Even in present day, literature addressing this topic wanes with less than 70 related publications between 2013-2023 (as determined via PubMed search for ‘(endometriosis[Title/Abstract]) AND (analgesic [Title/Abstract])’).

NSAIDs are commonly bought over the counter, or in some cases are prescribed, however, the dearth of information supporting their use for this purpose has remained constant across both the 2013 ESHRE guidelines and recent 2022 update2,3. Still, only one review appears to exist, citing many studies with poor overall data quality and wide confidence intervals, where results showed no statistically significant improvement in pain in response to treatment with NSAIDs like naproxen4. Furthermore, NSAID use is associated with significantly increased risk for gastrointestinal side effects (eg, nausea, diarrhea) and nervous system side effects (eg, drowsiness, dizziness), limiting their long-term use4. Interestingly, in vitro work in an endometriotic epithelial cell line revealed NSAID treatment increased the activity of MRP4 and its downstream target PGE2– a key signaling molecule implicated in pain, inflammation, and increased proliferation in endometriosis5,6 . While preclinical in nature, this data would seem to mechanistically support the limited efficacy of NSAIDs in treating endometrial pain.

Anti-depressants and anticonvulsants may also be used either alone or in combination with other treatments. However, similar to NSAIDs, there is limited evidence of efficacy and their use is further hindered by potentially severe dose-limiting side effects2. This guidance is further supported by a recent 2022 systematic review of the topic. In this study, Andrade, et al., revealed that while several publications demonstrated pain improvement on neuromodulators (such as gabapentin or amitriptyline), most of these had low evidence quality and small sample sizes. Furthermore, the more recent randomized controlled trial with the highest statistical power (N = 306) found no significant effect on pain scores in patients treated with gabapentin versus placebo7,8. These results further underscore the lack of evidence supporting the use of neuromodulators for endometriosis-related pain7.

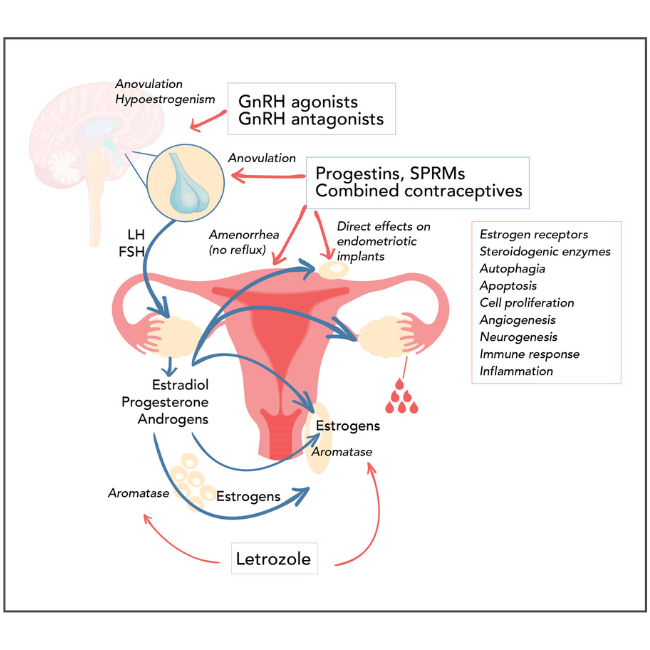

Hormone treatment is strongly recommended by the current, 2022 ESHRE guidelines. However, there have been changes from prior versions whereby certain agents are no longer recommended, and newer approved drug classes have been added based on demonstrated efficacy in recent clinical trials. Hormone treatment functionally relies on the steroid-dependent basis of endometriosis, as aberrant estrogenic activity drives hyperproliferation and inflammation. As highlighted in Figure 1, progesterone, gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH), and aromatase, therefore play key roles as mechanistic targets in the suppression of estrogen signaling underlying endometriosis progression and symptoms such as pain. Many of the existing and emerging therapies have varying safety profiles and different routes of administration, hence it is encouraged that clinicians employ shared decision making with patients in order to choose a regimen that best suits their individual needs, while also maintaining efficacy and minimizing side effects. Available treatment options covered in current guidelines include combined hormonal contraceptives, progestins, GnRH agonists, GnRH antagonists, and aromatase inhibitors.

Figure 1: Targets of hormone therapies in endometriosis (maybe an image as seen in this ref)

Combined hormonal contraceptive formulations of estrogen and progestin, often available as oral tablets (COCs), are recommended as a first-line treatment in the current ESHRE 2022 guidelines, and have been recommended similarly by guidelines from multiple other reproductive health societies.9 COCs control endometriosis-related pain in up to 80%-90% of treated patients, effectively reducing cyclical non-menstrual pain, dyspareunia and dyschezia, which facilitates overall significant improvements in patient QoL.2,10,11 These findings continue to be validated by the current literature. A recent prospective study of over 70 patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis on combination dienogest/ethinyl estradiol revealed treated patients experienced significant reductions in pain alongside improved overall and sexual quality of life after the 12-months trial period.12 In a second, recent retrospective cohort study, first-line treatment with estradiol valerate/nomegestrol acetate was shown to result in significantly reduced pain at 6-months in patients with ovarian and deep infiltrating endometriosis. Patients with ovarian endometrioma also experienced significant reduction in lesion size, where largest lesions shrunk from a median diameter of roughly 31mm to 13mm over 6 months.13 This well-established efficacy of COCs is further reflected through changes in the immune microenvironment, where a 2021 study revealed endometriotic tissue from COC-treated patients showed significantly reduced macrophage recruitment alongside increased numbers of T regulatory (Treg) and pro-apoptotic natural killer (NK) cells.14

COCs are generally considered safe, and are often widely available at low cost. These may be administered cyclically, or continuously, where guidelines highlight there are no significant differences in chronic pelvic pain reduction or dyspareunia between the two regimens, though continuous use may help patients achieve amenorrhea.2,15 Additional routes of administration beyond oral tablets are also available, including transdermal patches and vaginal rings, though with limited patient preference data available, guidelines do not make a recommendation of one mode over another.

Progestins are also guideline recommended as a first line therapy for the treatment of pain in endometriosis, and come in a variety of formulations including oral, depot (intramuscular and subcutaneous), implant, and intrauterine. Examples of commonly used progestins include dienogest, norethindrone/norethisterone acetate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and levonorgestrel.16 Functionally, progestins act in the hypothalamus to downregulate GnRH secretion, which subsequently inhibits FSH and LH activity responsible for ovulation. Long-term, this creates a hypoestrogenic environment also observable in the endometrium itself, where progestins have been shown to down-regulate expression of estrogen receptors.17 In vitro work has shown progestins inhibit estrogen-driven cell proliferation, inflammation, vascularization, and lesion innervation.17

Continuous progestin treatment has consistently been shown to be effective for reducing endometriosis pain, where reviews highlight no significant differences between varying oral formulations.2,18 More recent studies continue to demonstrate the efficacy of progestins, which often have similar results with respect to both pain and QoL when compared to COCs. For example, one 2021 randomized double-blind pilot of dienogest or COC versus placebo revealed both treatments resulted in significantly lower scores of pelvic pain and dyspareunia, alongside improved quality of life patients with severe endometriosis.19 A similar study in 2022 of dienogest versus ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone also demonstrated significant reductions in pain within both groups at 24 weeks compared to baseline, alongside concomitant improvements in quality of life, however, no significant differences between groups were found.20 Finally, a recent 2022 study of dienogest versus nomegestrol acetate/17β-estradiol (NOMAC) revealed similar results, wherein patients in both treatment groups experienced significant reductions in chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia at 12 months compared to baseline, alongside significant improvements to QoL. Overall efficacy of both agents was noted, where interestingly dienogest outperformed NOMAC at months 6 and 12 in SF-36 and FSFI scores of QoL and sexual function, respectively. 21 Side effects of progestin therapy vary by agent, dosage, and route of administration, though common side effects include headache, mood swings, acne, hot flushes, and weight gain.2,22 Present guidelines strongly recommend progestins for the treatment of endometriosis-related pain, in particular either a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or an etonogestrel-releasing subdermal implant, which have been shown to have equivalent clinical efficacy.2

It should be noted that danazol, previously recommended in 2013 ESHRE guidelines for second-line treatment, and by other societies as first-line, is no longer included in the updated 2022 ESHRE guidelines.2,9 Its high affinity for androgen receptors and moderate affinity for progesterone receptors lend itself to an exacerbated side effect profile including acne, edema, vaginal spotting, muscle cramps, deepening voice, and facial hair.2 Anti-progestins have similarly been removed from 2022 ESHRE guidelines.2

GnRH agonists, similar to prior years’ guidelines, remain recommended as a second-line treatment option for endometriosis-related pain due to their potential impact on bone mineral density, with an additional strong recommendation for add-back therapy to prevent bone loss.2,9 Mechanistically, prolonged GnRH agonist administration leads to a downregulation of GnRH receptors in the pituitary. This in turn suppresses FSH and LH activity in the ovaries and subsequent decline in estrogen production that would otherwise drive hyperproliferation and inflammation of endometriotic lesions.23,24 GnRH agonists are typically available as a nasal spray or injection (subcutaneous or intramuscular), with commonly used examples including leuprorelin, goserelin, nafarelin.

Historically, use of these agents has shown promising results for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain and endometriotic lesions. 2022 guidelines highlight a 2010 Cochrane review showed GnRH agonists were consistently more effective than placebo, with no differences between route of administration. While the 2010 review reported GnRH were inferior to the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and danazol, a 2023 Cochrane review highlights the reverse, where GnRH agonists may be slightly more efficacious in reducing pain compared to injectable progestins.2,25 Furthermore, a 2021 randomized trial comparing GnRH agonists (leuprorelin or triptorelin) to dienogest in post-surgical patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis revealed either treatment was significantly effective in reducing pelvic pain from baseline at 6 and 30 months, with no significant difference noted between groups.26 These results support the notable efficacy of GnRH agonists, however their side effect profile and cost may be a limiting factor in their overall use.

Common side effects of GnRH agonists include vaginal dryness, hot flushes, headache, decreased libido, and reduced bone mineral density.26 Over 6 months, bone mineral density may decrease by 2% to as much as 8%, however this is reversible and can be mitigated with “add-back” therapies like progestin monotherapy, estrogen-progestin combination, selective estrogen receptors, or bisphosphonate.2,27 A recent 2023 Cochrane review highlights slightly decreased in bone mineral density for patients on GnRH alone, compared to those on a GnRH with add-back regimen.25 These results, though with low-certainty evidence, appear to support guideline-highlighted data citing improved lumbar spine bone mineral density with GnRH agonists plus add-back therapy, with no drawbacks to efficacy in pain reduction when compared to GnRH agonist treatment alone.2,28

GnRH antagonists historically have not been guideline recommended, with the exception of the World Endometriosis Society 2013 guidelines, which provided only a weak recommendation for potential second-line treatment due to lack of sufficient evidence.9,29 GnRH antagonists work mechanistically to competitively block GnRH receptors in the pituitary, leading to an immediate suppression of LS and FSH signaling that promotes a hypoestrogenic environment.30 In the updated 2022 ESHRE guidelines these are now officially recommended for second-line treatment of endometrial pain, based on data from several studies leading to new approvals within this drug class for the treatment of endometriosis-related pain.2

Three common examples of GnRH antagonists include linzagolix, elagolix, and relugolix (which is administered as combination relugolix/estradiol/norethisterone acetate). While linzagolix is only approved presently within the EU, elagolix and relugolix combination therapy are both approved within the EU and US. All three have demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing endometriosis-related pain, supported by findings from a 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis by Yan et al. Elagolix and linzagolix were the two most commonly prescribed treatments for pain, whereas elagolix and relugolix were the top two prescribed treatments for dysmenorrhea. Authors highlight only high-dose treatments led to significantly improved quality of life, however at the cost of higher averse effect-related outcomes.31 These data mirror efficacy from Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials published within recent years. Relugolix monotherapy, for example, was shown to reduce pelvic pain over a 24-week period, with similar efficacy to that seen with leuprorelin treatment.32 In 2022 data published on the Phase 3 SPIRIT 1 and 2 studies, patients treated with relugolix combination therapy were significantly more likely to experience reduced dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain compared to patients on placebo alone, where treated patients also exhibited reduced opioid use.33 Initial data from the Elaris EM-1 and Elaris EM-II Phase 3 trials testing 150mg and 200mg of elagolix versus placebo revealed treated women experienced higher rates of response with respect to dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain at 3- and 6-months. Patients in the highest dose group (200mg) were more likely to experience therapeutic benefit overall, with less dyspareunia at 3 months, and were less likely to rely on rescue analgesics and opioids.34 Follow-up extension studies Elaris EM-III and Elaris EM-IV continued to demonstrate elagolix efficacy for treated patients in either dose group at 12 months of treatment.35 2020 data revealed this clinical benefit translated to patient QoL, where patients with clinically meaningful dyspareunia response showed significant improvements in feelings of control and powerlessness, emotional well-being, self-image, pain, sexual intercourse, and social support.36

Side effects associated with GnRH use include hot flushes, headache, and nausea, where these are generally considered to be mild. Bone mineral loss has also been noted with GnRH antagonists, and as such add-back therapy has also been suggested for this drug class; however, with limited evidence, guidelines do not presently make recommendations to this effect.2,32,35,37

Aromatase inhibitors such as letrozole and anastrozole, are recommended for treatment of endometriosis-related pain, largely as a third-line approach. Functionally, these inhibit aromatase conversion of androgens to estrogens, suppressing estrogenic-based pathways that promote hyperproliferation and inflammation. Long-term outcomes on the efficacy and safety of aromatase inhibitors in endometriosis is lacking, though data from studies with short treatment durations has shown promising results. In a prospective cohort study, 3 months of treatment with letrozole with progestin add-back therapy led to significant reductions not only in patient non-menstrual pain and dyspareunia, but also in mean lesion size, with a diameter shrinkage of on average 50%.38 Such results continue to be replicated in recent case reports, where one such study with a corresponding review highlights single-agent letrozole yields excellent clinical response and may be especially applicable for treating refractory, recurring, and deep infiltrating endometriosis that involves the rectum and urinary tract.39 Side effects associated with aromatase inhibitor use result from the hypoestrogenic environment, and therefore similarly include vaginal dryness, hot flushes, and reduced bone mineral density. However, due to its role in ovulation, aromatase inhibitor use may also facilitate situations of multiple gestation. Due to the comparatively more severe side effect profile for these drugs, guidelines recommend their use in situations where all other medical or surgical treatment has failed.2

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a challenging disease to treat with respect to pain. Analgesics like NSAIDs are weakly recommended due to the dearth of evidence on their efficacy and control of disease progression, alongside a negative side effect profile limiting long-term use. Hormonal treatments, in particular combined hormonal contraceptives and progestins, are guideline recommended for first-line treatment of endometriosis, and have consistently demonstrated a favorable efficacy and safety profile. Up to 33% of patients, however, may fail to respond to these regimens, warranting the use of second-line GnRH agonists/antagonists, or aromatase inhibitors (where available). Collectively all hormonal treatments are designed to target pathways involved in estrogen signaling and activity, promoting a hypo-estrogenic environment. These therapies often have different routes of administration, differing mechanisms of action, and therefore varying safety profiles. It is therefore important that clinicians be aware of the updated landscape for endometriosis-related pain so that they may better communicate with patients and engage in shared decision making to select appropriate treatment options.

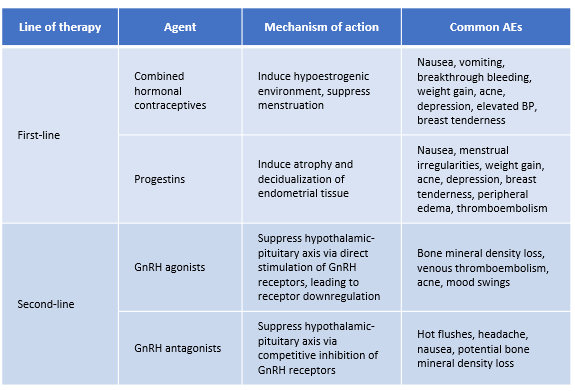

Table 1. Maybe incorporate a brief summary table of the drug type, 1L/2L/3L; common examples of drugs used for each category and ROA, common side effects

1. Cetera GE, Merli CEM, Facchin F, et al. Non-response to first-line hormonal treatment for symptomatic endometriosis: Overcoming tunnel vision. A narrative review. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):347-1. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02490-1.

2. Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022;2022(2):hoac009. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac009.

3. Dunselman GAJ, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis †. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det457. Accessed 9/1/2023. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457.

4. Brown J, Crawford TJ, Allen C, Hopewell S, Prentice A. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain in women with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1(1):CD004753. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004753.pub4.

5. Massimi I, Pulcinelli FM, Piscitelli VP, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase MRP4 expression in an endometriotic epithelial cell line in a PPARa dependent manner. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(23):8487-8496. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201812_16549.

6. Sacco K, Portelli M, Pollacco J, Schembri-Wismayer P, Calleja-Agius J. The role of prostaglandin E2 in endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28(2):134-138. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2011.588753.

7. Andrade MA, Soares LC, Oliveira MAPd. The effect of neuromodulatory drugs on the intensity of chronic pelvic pain in women: A systematic review. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2022;44(9):891-898. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1755459.

8. Horne AW, Vincent K, Hewitt CA, et al. Gabapentin for chronic pelvic pain in women (GaPP2): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10255):909-917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31693-7.

9. Kalaitzopoulos DR, Samartzis N, Kolovos GN, et al. Treatment of endometriosis: A review with comparison of 8 guidelines. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):397-5. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01545-5.

10. Brown J, Crawford TJ, Datta S, Prentice A. Oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD001019. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001019.pub3.

11. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(5):261-275. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.255.

12. Alcalde AM, Martínez-Zamora MÁ, Gracia M, et al. Assessment of quality of life, sexual quality of life, and pain symptoms in deep infiltrating endometriosis patients with or without associated adenomyosis and the influence of a flexible extended combined oral contraceptive regimen: Results of a prospective, observational study. J Sex Med. 2022;19(2):311-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.11.015.

13. Mariani LL, Novara L, Mancarella M, Fuso L, Casula E, Biglia N. Estradiol/nomegestrol acetate as a first-line and rescue therapy for the treatment of ovarian and deep infiltrating endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021;37(7):646-649. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2021.1903420.

14. Waiyaput W, Wattanakamolchai K, Tingthanatikul Y, et al. Effect of combined contraceptive pill on immune cell of ovarian endometriotic tissue. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14(1):66-8. doi: 10.1186/s13048-021-00819-8.

15. Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Pietropaolo G, Pasin R, Crosignani PG. Continuous use of an oral contraceptive for endometriosis-associated recurrent dysmenorrhea that does not respond to a cyclic pill regimen. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(3):560-563. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00794-5.

16. Barbieri R. Optimize the medical treatment of endometriosis—Use all available medications. OBG Manag. 2018;8(8):12-13. https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/171593/gynecology/optimize-medical-treatment-endometriosis-use-all-available.

17. Reis FM, Coutinho LM, Vannuccini S, Batteux F, Chapron C, Petraglia F. Progesterone receptor ligands for the treatment of endometriosis: The mechanisms behind therapeutic success and failure. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26(4):565-585. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmaa009.

18. Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(3):CD002122. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002122.pub2.

19. Mehdizadeh Kashi A, Niakan G, Ebrahimpour M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the comparative effects of dienogest and the combined oral contraceptive pill in women with endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;156(1):124-132. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13677.

20. El Taha L, Abu Musa A, Khalifeh D, Khalil A, Abbasi S, Nassif J. Efficacy of dienogest vs combined oral contraceptive on pain associated with endometriosis: Randomized clinical trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;267:205-212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.10.029.

21. Caruso S, Cianci A, Iraci Sareri M, Panella M, Caruso G, Cianci S. Randomized study on the effectiveness of nomegestrol acetate plus 17β-estradiol oral contraceptive versus dienogest oral pill in women with suspected endometriosisassociated chronic pelvic pain. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):146-7. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01737-7.

22. Gezer A, Oral E. Progestin therapy in endometriosis. Womens Health (Lond). 2015;11(5):643-652. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.42.

23. Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. In: LiverTox: Clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547863/. Accessed Sep 1, 2023.

24. Olive DL. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1136-1142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0803719.

25. Veth VB, de Kar M, Duffy JM, Wely M, Mijatovic V, Maas JW. Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone analogues for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2021(7):CD014788. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014788. eCollection 2021. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014788.

26. Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Liverani S, et al. Dienogest vs GnRH agonists as postoperative therapy after laparoscopic eradication of deep infiltrating endometriosis with bowel and parametrial surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021;37(10):930-933. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2021.1929151.

27. Resta C, Moustogiannis A, Chatzinikita E, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)/GnRH receptors and their role in the treatment of endometriosis. Cureus. 2023;15(4):e38136. doi: 10.7759/cureus.38136.

28. Wu D, Hu M, Hong L, et al. Clinical efficacy of add-back therapy in treatment of endometriosis: A meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(3):513-523. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3230-8.

29. Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium. Consensus on current management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(6):1552-1568. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det050.

30. Rzewuska AM, Żybowska M, Sajkiewicz I, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists-A new hope in endometriosis treatment? J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):1008. doi: 10.3390/jcm12031008. doi: 10.3390/jcm12031008.

31. Yan H, Shi J, Li X, et al. Oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists for treating endometriosis-associated pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(6):1102-1116. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.08.856.

32. Osuga Y, Seki Y, Tanimoto M, Kusumoto T, Kudou K, Terakawa N. Relugolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonist, in women with endometriosis-associated pain: Phase 2 safety and efficacy 24-week results. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):250-3. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01393-3.

33. Giudice LC, As-Sanie S, Arjona Ferreira JC, et al. Once daily oral relugolix combination therapy versus placebo in patients with endometriosis-associated pain: Two replicate phase 3, randomised, double-blind, studies (SPIRIT 1 and 2). Lancet. 2022;399(10343):2267-2279. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00622-5.

34. Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28-40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700089.

35. Surrey E, Taylor HS, Giudice L, et al. Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: Results from two extension studies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):147-160. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002675.

36. Agarwal SK, Soliman AM, Pokrzywinski RM, Snabes MC, Coyne KS. Clinically meaningful reduction in dyspareunia is associated with significant improvements in health-related quality of life among women with moderate to severe pain associated with endometriosis: A pooled analysis of two phase III trials of elagolix. J Sex Med. 2020;17(12):2427-2433. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.08.002.

37. Donnez J, Dolmans M. GnRH antagonists with or without add-back therapy: A new alternative in the management of endometriosis? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11342. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111342. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111342.

38. Agarwal SK, Foster WG. Reduction in endometrioma size with three months of aromatase inhibition and progestin add-back. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:878517. doi: 10.1155/2015/878517.

39. Rotenberg O, Kuo DYS, Goldberg GL. Use of aromatase inhibitors in menopausal deep endometriosis: A case report and literature review. Climacteric. 2022;25(3):235-239. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2021.1990259.